Dr. David Bowering, MD, MHSc, was for 25 years a Medical Health Officer (now retired) of the Northern Health Authority in the province of British Columbia. He was the Chief Medical Health Officer for a decade. He oversaw public health in a region of nearly 600,000 square kilometres and was in that role during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009.

I think it is time that we talked to each other about the pandemic.

We have been through the three most troubling and transformative years of most of our lives. Everything began to change for almost everyone when the WHO declared the early COVID-19 outbreaks in China and Italy and on some cruise ships, along with a smattering of cases elsewhere, to be a global pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus, SARS‑CoV‑2.

Although we frequently hear people refer to the pandemic as if it were an objective event that happened to all of us, the truth is that there were as many COVID experiences as there are people. The official version of the COVID story relied on simplified memes designed to trigger fear and to make us compliant. But the truth is we are complex creatures living in an infinitely complex and beautiful world. “One size fits all” is not only simplistic and misleading, it is a defining characteristic of life in a tyrannical dystopia.

Because of my 40-year career in medicine and public health, my initial focus was on the public health response and on the manner in which my former colleagues, especially those who specialized in infectious diseases, were suddenly thrust into positions of godlike authority that I knew very well went far beyond what they were trained for or were capable of handling.

I had been fortunate in my medical school training to have been taught by a radical group of pharmacology teachers at UBC in the late '60s who taught us to be wary of the tricks and machinations of drug companies. We would soon graduate with the keys to the drug cupboard in our hands, and without us, those companies would have no means of getting their products into the hands and bodies of consumers. It was our job to be vigilant gatekeepers, but in a very real sense, we were acting as agents for the pharmaceutical industry the moment we began to write prescriptions.

My grooming began on graduation day with each member of my class receiving a black leather medical bag containing a stethoscope, a state of the art rechargeable ophthalmoscope, and a reflex hammer from Eli Lilly. Every doctor throughout their career knows about the dinners, the free education sessions, the trips, the conferences, the drug samples and the wine-toting charms of the drug company sales representatives who just keep showing up.

My public health career began in 1984 as a Field Epidemiologist for the Canadian version of the CDC, known as the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control. In those early days, I encountered vaccine industry friendliness that went beyond what I had previously known as a general practitioner. It made sense considering the vast monetary difference between prescribing a drug for one patient at a time and prescribing a vaccine that might be given to millions of customers and entire cohorts of the population year after year.

Over three decades in public health, I attended multiple vaccine conferences, mostly if not entirely funded by Pharma. I had lovely meals, lovely drinks, lovely post-conference entertainment and social events, and I accumulated a small mountain of swag. The mug I was sipping coffee from while making decisions about vaccines was almost sure to have a vaccine company logo on it, as were the pens I signed forms with, and the briefcases I carried my reports and my computer in.

A cozy relationship with the vaccine manufacturers is part of the culture of public health. Every public health doctor has to come to terms with it. Many of us imagined that we were above flattery and persuasion and that the thousands of dollars spent on each of us every year had no influence on our thinking or our practices. Silly multibillion-dollar drug companies to waste their money on us like that!

It was almost impossible to work in public health without believing – with a conviction bordering on naivety – that the regulatory agencies and processes they use are free from corporate and political influence, that revolving doors between regulators and industry don't matter, or that vaccine hesitancy is a form of mental illness, if not a dangerous form of social deviance. We were the good guys who believed in preventing rather than just treating sickness. It’s hard to imagine a more malleable group from the perspective of a drug company with enormous wealth, all the persuasive cunning that money can buy, and no ethical framework whatsoever beyond dominating the marketplace.

One of the most frightening things for me now, as someone who once spent his mornings writing notes to the parents of children who reported adverse vaccine reactions – telling them that whatever took place was “expected” or “within normal limits” – is that I now recognize just how strong the public health bias against acknowledging vaccine adverse reactions and negative outcomes actually is. The standard of proof in relation to acknowledging vaccine harm is so high that for all intents and purposes it can't be met.

Occasionally I would send a worrisome case on for further evaluation through a poorly defined vetting process. This involved the calling in of experts, over a period of months and even years, who almost inevitably reached the conclusion that due to the complexity of the immune system, other possible explanations including coincidence could not be ruled out. “No evidence of harm” became synonymous in our thinking with “evidence of safety.” The financial repercussions for vaccine companies if their products are acknowledged to do harm are immense. For public health professionals, an acknowledged harm carries the potential for a loss of public support for our campaigns along with damage to our good-guy reputations.

That was the case in normal times, but it helps me to understand how, even in the face of the glaring red flags in the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) after the mRNA shots were rolled out, the mantra of “safe and effective” never wavered. I don't know of anyone who has done a more thorough analysis of VAERS data than the Canadian immunologist and molecular biologist Jessica Rose, for readers wanting to know more. See for example VAERS Update for the CCCA and her recent look at the data.

I have never been an ‘anti-vaxxer’, any more than an Anglican is an ‘anti-Christian’ because she doesn't happen to be a Bible-thumping fundamentalist. But I continue to re-evaluate many of the old vaccine narratives as I see how effective the current marketing blitz has been at distorting informed debate and critical thinking about these new ones.

With my background of acquired skepticism toward drug companies, with my inherent preference for health promotion and empowerment over enforcement and the creation of dependencies, and with my golden handcuffs gathering dust on the shelf, I watched the COVID train wreck unfold.

In early 2020, I heard the Canadian CEO of Pfizer interviewed on CBC radio as he announced that his new product, although at the time almost impossible to use due to its cold-chain requirements, had won the race to market. He called it “the most precious substance on earth,” and the CBC lapped it up, repeating the word “vaccine” hundreds of times a day, month after month. So did our Prime Minister, who announced the signing of agreements with Pfizer to purchase more than enough for every Canadian, along with the usual undisclosed agreements for future purchases and no product liability for Pfizer.

The parade of Chief Medical Health Officers standing side by side with their political masters, singing in chorus from the same song sheet, using catch phrases repeated by their colleagues around the world, had begun. With the mainstream media hanging on every word, a simple story swept the globe: that humankind was at risk and could only be saved through “the science” – defined as whatever these people said. This compelling story stopped the world as we knew it.

I look forward to writing in this space and thinking about what happened after that when so many things we thought we knew began to shift and come unglued. I hope we can find our way to honest and open discussion about the world we now face and begin to see things in a more collaborative and constructive way. Perhaps it is still possible to offer hope for a better world to our grandchildren.

COVID has shown us what can happen if we let fear and the purveyors of fear control our stories. There is no doubt that there is more of the same where COVID came from, but if we celebrate our humanity and our shared connections with each other and with the natural world, and if we are confident and vigorous in doing so, it will not go quite so well for the Ministry of Truth next time around. I can't wait to read what the other contributors to this substack will have to say.

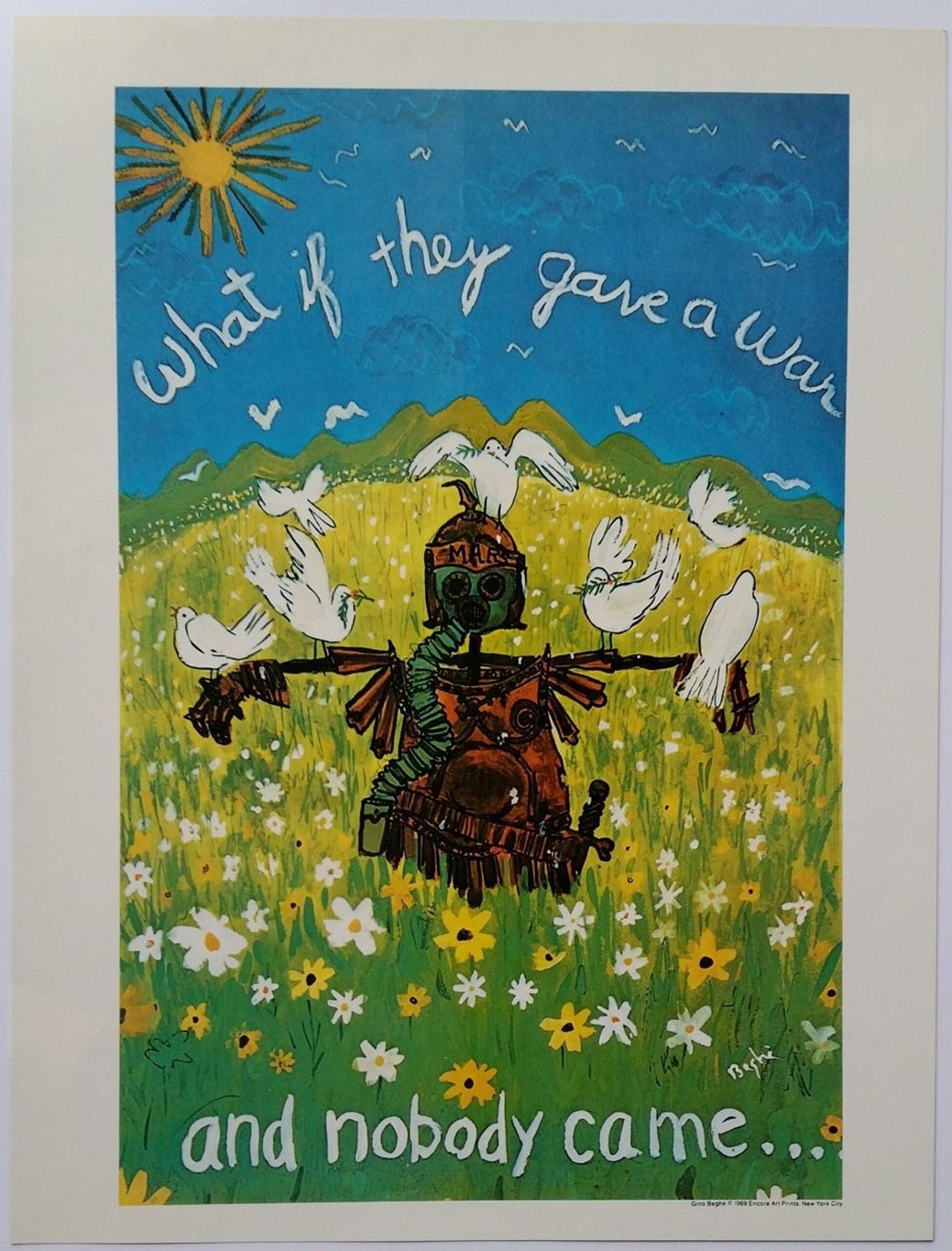

The topic that springs to mind for next time is “war” and our habit of declaring war on anything that seems to be a problem. To paraphrase an old slogan: “What if they gave a pandemic and nobody came?”